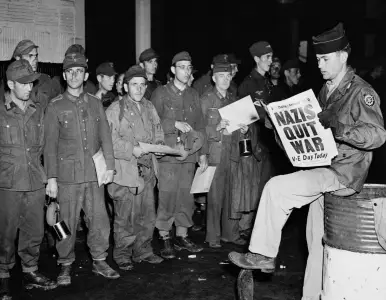

Lucas: German POWs found fresh start in America after WWII

The influx of immigrants crossing our border under President Biden’s watch isn’t the first time the U.S. has hosted foreign nationals en masse. During WWII, 400,000 German soldiers made the U. S. their home. They were prisoners of war, and they were here because there was no place else to put them. Great Britain was living on the edge with no space, food or manpower to spare. So, they lived out their wartime imprisonment in six hundred mostly hastily built — and now forgotten — POW camps that stretched across the U.S., from Massachusetts (Cape Cod, Ft. Devens) to California, with many camps in Texas, Georgia and Arkansas. The prisoners, officers excluded, provided the country with manpower, partially filling the roles of young American men serving in the military. The POWS herded cattle and tended crops in Kansas, Iowa, North Carolina and elsewhere. They worked in forestry in Maine and New Hampshire and as cowboys in Texas. While many of the officers and noncoms were hard-core Nazis, the bulk of the soldiers were not. Nevertheless, it was the Nazis who often ruled the internal workings of the camps issuing punishment that included murder. The first batch of prisoners came following the Allied defeat of the General Erwin Rommel’s vaunted Afrika Korps in North Africa in May 1943. The allied victory came following the U.S. invasion in November 1942 called Operation Torch. It was, along with the Russian defeat of the Germans at Stalingrad, a sign of things to come in the final defeat of Hitler’s Germany. Some 170,000 German soldiers, including 12 generals, were taken prisoner following the battle and shipped to the United States to be housed. Soon thousands more would arrive in a country that had not dealt with prisoners of war to any extent since the Civil War. As the U.S. and Germany were signatories of the Geneva Convention, the German prisoners were treated well in the hope that American prisoners of war held in Germany and Japan would also be treated well. It was often was not the case. The good treatment accounted for why there were relatively few attempts to escape. Besides, America was too vast. Only one German escapee made his way back to Germany to rejoin the war. This determined German walked out of a camp in Oklahoma, hitchhiked a ride to Baltimore, talked his way onto a freighter bound for Lisbon, crossed Portugal and Italy to Germany. He was later recaptured before he could dream of opening a travel agency. All of this and more is told in William Geroux’s book “The Fifteen,” which is about “Murder, Retribution and the Forgotten Story of NAZI POWs in America.” The dark side of the story was the murder by rabid Nazis — hangings and death by beating — of scores of fellow prisoners who were accused of faltering belief in Hitler and Nazism. The Nazis set up secret squads in the camps to conduct beatings and killings of prisoners thought to be too friendly with U.S. officials or were accused of being informers. The U.S. would eventually arrest, and with due process, court martial 15 die-hard Nazis on murder charges. All were sentenced to hang. When Hitler’s Third Reich learned through the Swiss of the sentencing, it ordered death sentences for 15 American prisoners of war on bogus charges of war crimes. Fourteen of the convicted Nazis were hanged, while the fifteenth had his sentenced commuted to 20 years by President Harry Truman. The 15 Americans escaped execution because Nazi Germany collapsed, Hitler shot himself and Germany surrendered. The prisoners were sent home. However, some five thousand returned to the U.S and became doctors, lawyers, artists and set up businesses. Gerd Kruse, an Afrika Korps artilleryman, said, “When I set foot on German soil and saw what happened, I just as soon turned around.” He married an American and ran the family farm. Frieda Goedecke, who set up a manufacturing company and a retail store with her husband Heinrich, who was a prisoner, said “You can do it here in America. I think that is the only place you can do it.” Veteran political reporter Peter Lucas can be reached at: [email protected] In this handout from the U.S. Army, German prisoners of war interned at Camp Blanding, near Jacksonville, Fla., exercise on the horizontal bar, July 2, 1943. (AP Photo/U.S. Army)