Google Secretly Handed ICE Data About Pro-Palestine Student Activist

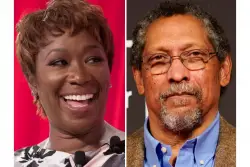

Even before immigration authorities began rounding up international students who had spoken out about Israel’s war on Gaza earlier this spring, there was a sense of fear among campus activists. Two graduate students at Cornell University — Momodou Taal and Amandla Thomas-Johnson — were so worried they would be targeted that they fled their dorms to lay low in a house outside Ithaca, New York. As they feared, Homeland Security Investigations, the intelligence division of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, was intent to track them both down. As agents scrambled to find Taal and Thomas-Johnston, HSI sent subpoenas to Google and Meta for sensitive data information about their Gmail, Facebook, and Instagram accounts. In Thomas-Johnston’s case, The Intercept found, Google handed over data to ICE before notifying him or giving him an opportunity to challenge the subpoena. By the time he found out about the data demand, Thomas-Johnston had already left the U.S. During the first Trump administration, tech companies publicly fought federal subpoenas on behalf of their users who were targeted for protected speech — sometimes with great fanfare. With ICE ramping up its use of dragnet tools to meet its deportation quotas and smoke out noncitizens who protest Israel’s war on Gaza, Silicon Valley’s willingness to accommodate these kinds of subpoenas puts those who speak out at greater risk. Lindsay Nash, a professor at Cardozo School of Law in New York who has studied ICE’s use of administrative subpoenas, said she was concerned but not surprised that Google complied with the subpoena about Thomas-Johnston’s account without notifying him. “Subpoenas can easily be used and the person never knows.” “Subpoenas can easily be used and the person never knows,” Nash told The Intercept. “It’s problematic to have a situation in which people who are targeted by these subpoenas don’t have an opportunity to vindicate their rights.” Google declined to discuss the specifics of the subpoenas, but the company said administrative subpoenas like these do not include facts about the underlying investigation. “Our processes for handling law enforcement subpoenas are designed to protect users’ privacy while meeting our legal obligations,” said a Google spokesperson in an emailed statement. “We review every subpoena and similar order for legal validity, and we push back against those that are overbroad or improper, including objecting to some entirely.” ICE agents sent the administrative subpoenas to Google and Meta by invoking a broad legal provision that gives immigration officers authority to demand documents “relating to the privilege of any person to enter, reenter, reside in, or pass through the United States.” One recent study based on ICE records found agents invoke this same provision hundreds of times each year in administrative subpoenas to tech companies. Another study found ICE’s subpoenas to tech companies and other private entities “overwhelmingly sought information that could be used to locate ICE’s targets.” Unlike search warrants, administrative subpoenas like these do not require a judge’s signature or probable cause of a crime, which means they are ripe for abuse. Silicon Valley’s willingness to accommodate these kinds of subpoenas puts those who speak out at greater risk. HSI had flagged Taal to the State Department following “targeted analysis to substantiate aliens’ alleged engagement of antisemitic activities,” according to an affidavit later filed in court by a high-ranking official. This analysis amounted to a trawl of online articles about Taal’s participation in Gaza protests and run-ins with the Cornell administration. The State Department revoked Taal’s visa, and ICE agents in upstate New York began searching for him. In mid-March, the week after Mahmoud Khalil was arrested in New York City, Taal sued the Trump administration, seeking an injunction that would have blocked ICE from detaining him too. By this point, he and Thomas-Johnston had both left their campus housing at Cornell and were hiding from ICE in a house 10 miles outside Ithaca. Two days after Taal filed his suit, still unable to track him down, ICE sent an administrative subpoena to Meta. According to notices Meta emailed to Taal, the subpoena sought information about his Instagram and Facebook accounts. Meta gave Taal 10 days to challenge the subpoena in court before the company would comply and hand over data about his accounts to ICE. Like Google, Meta declined to discuss the subpoena it received about Taal’s account, referring The Intercept to a webpage about the company’s compliance with data demands. A week later, HSI sent another administrative subpoena to Google regarding Taal’s Gmail account, according to a notice Google sent him the next day. “It was a phishing expedition,” Taal said in a text message to The Intercept. After Taal decided to leave the country and dismissed his lawsuit in April, ICE withdrew its subpoenas for his records. But on the last day of March, HSI sent yet another subpoena, this one to Google for information about Thomas-Johnson’s Gmail account. Without giving Thomas-Johnston any advance warning or the opportunity to challenge it, Google complied with the subpoena, and it only notified him weeks later. “Google has received and responded to legal process from a Law Enforcement authority compelling the release of information related to your Google Account,” read an email Google sent him in early May. By this point, Thomas-Johnston had already left the country too. He fled after a friend was detained at the Tampa airport, handed a note with Thomas-Johnston’s name on it, and asked repeatedly about his whereabouts, he told The Intercept. Thomas-Johnston’s lawyer, who also represented Taal, reached out to an attorney for Google about the demand for his client’s account information. “Google has already fulfilled this subpoena,” Google’s attorney replied by email, further explaining that Google’s “production consisted of basic subscriber information,” such as the name, address, and phone number associated with the account. Google did not produce “the contents of communications, metadata regarding those communications, or location information,” the company’s attorney wrote. “This is the extent that they will go to be in support of genocide,” Taal said of the government’s attempts to locate him using subpoenas. The post Google Secretly Handed ICE Data About Pro-Palestine Student Activist appeared first on The Intercept.